1. Solving System Problems with Limited Time, Resources, and Understanding

Systems-thinking in practice

How do you solve for system-level problems with limited time, resources, and understanding? When customers use a company’s product suite, they don’t care if the product is segmented across teams…they see it as one user experience. Customer satisfaction is anchored by weak links and inconsistencies, even if some user flows work well. Seeing the product suite as one experience allows builders to take ownership and ask strategic questions.

I encountered this question when digitizing mortgage investing. After people buy homes, they send monthly payments to investors until their loan is paid off.1 At nCino Mortgage, my team and I created the eVault platform where these financial players buy, sell, and register loans. Though the eVault sat at the end of the overall user experience, we needed to learn how it connected to the big picture to link design and code cohesively. Our persona worked with other personas, so how we facilitated their collaboration across products directly impacted user satisfaction.ity to navigate constraints like quick turnarounds, understaffed teams, and communication siloes.

That’s where systems thinking requires a crafter approach to create positive change.

Strategic measures such as overall loan management speed and customer satisfaction required a deep understanding of the system and the ability to navigate constraints like quick turnarounds, understaffed teams, and communication siloes.

That’s where systems thinking requires a crafter approach to create positive change.

What is systems thinking?

Systems thinking2 is the ability to see an element (like a user, task, or product) and relate it to its parts, looking deeper into the details or stepping back to see the bigger picture.

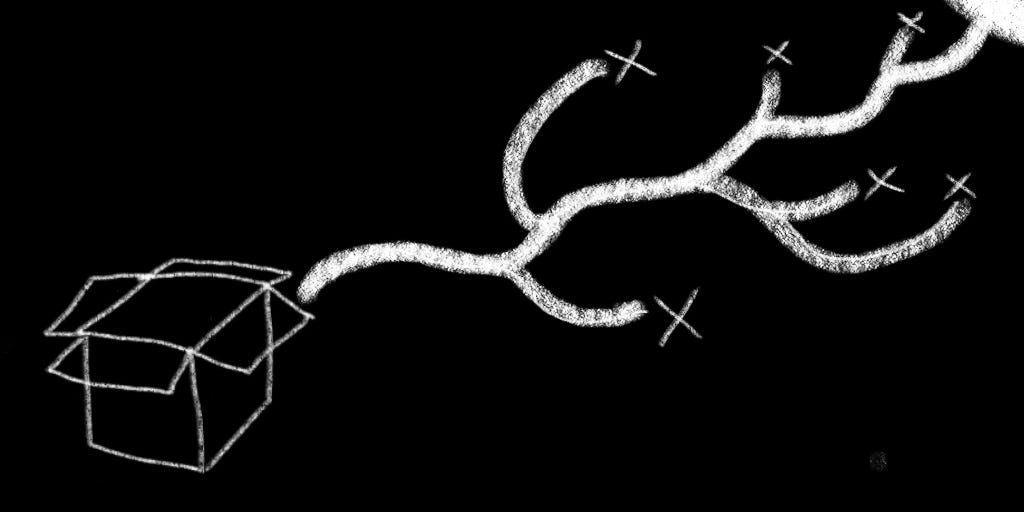

Imagine, if we zoom out, a tree is part of a forest, which can be part of an island, which can be part of a chain of islands, which can be part of a marine ecosystem.3

If we zoom in, a tree has roots, which has nutrients, which contain elements like phosphorous, nitrogen, and potassium.

Zooming in and out, oscillating flexibly while maintaining context of the stakeholders and circumstantial needs, allows us to identify solutions that can address multiple needs at once, a holistic way of solving problems.

Over time, we develop a wide and deep understanding of problem, players, incentives, forces, and environments. This knowledge is the basis for UX product strategy.

Showing is more convincing than telling. Visualizing this information as a map or diagram simplifies cross-team collaboration. Since people’s perspectives differ across disciplines, visual representations are more efficient than verbal explanations to understand problems in its rich depth and nuance. Representing each perspective and showing how they connect to the problem eases the buy-in process, as stakeholders can see your effort and correct if needed. This is a great time to gather feedback with stakeholders to identify missing information or nuances.

Reflecting new information in the visual helps document the process for continuous team alignment over time. It also shows people how their engagement impacts the project, building camaraderie and a sense of progress. This practice emphasizes that the visual is an asset that can serve as a source of truth.

After alignment, your conversations grow to be strategic. Now that everyone understands the What, you can move onto the Now What. People will be eager to provide solutions, but designers can guide brainstorms to be imaginative and innovative. You can explore unknowns and hopefully push forward to uncover unknown-unknowns, risk and challenges you don’t know of but are uncovered in the process. Facilitating workshops is out-of-scope for this article, but it is a powerful skill that expands creative collaboration, compounding on your systems thinking.

Applying systems thinking across work environments

Startups start bottom-up, still learning who their customers are, what problems they have, and how to solve problems to make sales. Speed is a higher priority to its success than scale and organization. Documenting insights of successful and unsuccessful experiments, valuable ways of working, and hard-earned lessons help build operational processes in later-stage growth; however, I’ve made the mistake of prioritizing process over speed and profit too early. It’s not immediately helpful, so the cost of time and energy is higher than documentation in larger settings.

In corporate environments, systems thinking is necessary to solve disjointed horizontal problems. An example is storytelling across a customer’s experience. If Marketing and Sales are aligned but narratives are not reflect in the products’ UX copy, customers can be confused. This dissonance can render into drop-off engagement, dissatisfaction, or misunderstandings of your product’s usefulness. Hopefully at this stage, you can dive into your company’s existing documentation, connect dots to burning questions, and survey unexplored opportunities while improving user experience. This knowledge can support how you show up whether you’d like to lead or create holistically.

Case study: Siloed teams and horizontal problems

How does a designer apply deep thinking, foresight, and strategy when change is rapid? When I started at nCino Mortgage, my job was to create products so the company could invest in new markets. I didn’t know how mortgage worked, how product teams connected their user experiences, and what place we had in the market. I became a sponge absorbing what was known by my teams and our company, scouring documentation and asking many questions.

I created user journey maps which helped my team communicate and make decisions that scaled our growth. Decisions compounded to save us time and energy in the long run. Similar problems were given similar treatment, speeding our output. When we made a structural change in one area, we thought about other areas that needed updating. Proactive changes prevented tech debt and overhead effort later.

By understanding technical details (how our tech stack and data works) and user needs (in our user group), we were able to scale decision-making across the team. Having shared knowledge of how we solve problems and important use cases proved to be a team advantage; when other teams asked us questions, any of us can answer with trust in our unified response.

Building collective understanding can also be done by unifying designers and connecting their knowledge through dialogue, workshops, and critique. Designers operate horizontally, so they can understand what users see and score when grading overall experience. As designers work with product managers, this knowledge can influence common areas of growth. For instance, if Designer A is working on Notifications, they can ask Designer B, C, and D what they’re seeing in terms of user frustrations. Those insights can be incorporated into talks with Product Manager A, and the duo can add an update that improves Team B, C, and D’s parts of the user experience.

This is a win-win-win as the product can make bigger impact while lessening debt for multiple teams with fewer resources, and improve the overall product suite (and cross-team camaraderie!).

After seeing our team grow, I realized that my disjointed understanding at the start was a common challenge in large organizations. Siloed teams (e.g., those split to own select user types and product areas) create siloed information and divergent approaches to similar problems, which compounded into siloed user experiences. This communication decay affects companies slowly until you realize they stopped innovating, banking on old product.

Systems mapping in practice

Knowing how you impact a system and vice versa allows you to imagine downstream effects and anticipate incoming challenges. Constraints, incentives of user behavior, and leverage points for change inform strategy and improve impact (finding your best bang for your buck!).

Imagine you are joining a new environment. Whether it be a new company, team, or project, you are starting at baseline.

Start by exploring your current map

Take a deep look at where you’re standing now.

What do you, your team and company know about the problems, players, products, and market?

What is the problem? What happens before and after the problem? What does this look like in users’ experience(s)?

Who are the players: stakeholders, users, internal and external? How is everyone related? Who is the ultimate boss? Who needs to be pleased? Who will help you shepard your designs to the finish line? Who will help you find the truth and gather feedback?

Step outside

Explore what else is known by your team, company, or market to gain a wider understanding of the context(s). Create a visual map of what you know, something that can communicate information to anyone. I typically use User Journeys and Relationship Maps. Mapping what’s in the tech stack and seeing where data you’re working with is also useful (Ask your developers for any diagrams they have).

What else? Can you see where your company sits in the market? What do people say about your product? What problems are in the industry? Market research is a low-cost way of answering relevant questions.

What about where your product sits in the product suite?

Or how your team functions in relation to the business like customer success, sales, and support?

Analyze the information as a whole

Find patterns, hot spots, and potential areas for discovery. By marking specific opportunities, you can imagine what change can look like.

How are people incentivized and how does that affect their behavior and relationships?

See any bottlenecks or leverage points that impact users’ speed, ease, trust or likelihood of delinquency?

Can you observe the system like a helicopter flying around islands or a magnifying glass on dirt?

Imagine and define Better

Vividly imagine and define ideal user experience and its intended outcome. Illustrating the change required to reach that vision, considering upsides and tradeoffs. Prototyping is a powerful motivator to anchor imagination into higher ground. Showing how the vision translates into story beats, or moments in the customer journey, inspires collaborators to also strive outside of their comfort zones.

Think and brainstorm alone and with others. It’s important to carve your ideal without constraints, then bring it to others for feedback and advice, instead of the other way around. If constraints chop ideas down to reality, keeping a high vision allows more wiggle room in compromise.

Consider where the business, industry, and user sentiments are going. If there’s a cultural wave moving, you want to know about it. Even the strongest product can flop if the market is not ready for it.

Chart another path

Visions are constrained by reality, but if leverage points are identified, prioritized, and persuaded to key stakeholders, it’s possible to adapt constraints to assert stronger solutions. A steady plan understands who is involved, and how to motivate and track improvements. Having a sense of progress is a powerful motivator even if the vision looks impossible.

Can you and your team organize the opportunities by impact and effort then prioritize accordingly? Constraints will influence priority, so defining and communicating your recommendations can influence strategy to address user needs with the bottom line.

How should people work together to yield the ideal? Bringing key collaborators early can build the trust needed to think holistically and make projects smoother and more enjoyable.

Designers have a unique advantage as horizontal functions with strong visual and critical thinking skills. Illustrating information without losing nuance, telling stories that connect strategy to visions, and pitching humane futures are powerful enablers to holistic business solutions.

These skills also grow collective understanding and foster discovery which nurture organizational culture. It takes many skilled people to create holistic solutions that consider the needs of all stakeholders, business, and user needs while understanding the dynamics of how change moves through a system.

Sometimes homeowners send their payments to Servicers, a customer-service front who handle loan payments for Investors. Mortgage loans are reliable investments over time if you’re a big bank or government entity, especially in cases like the 30-Year Fixed loan structure.

Excellent Farnam Street article on systems thinking mental model definitions

Eames’ “Power of Ten” 1977 video, made for IBM, is useful visual to understand this mental model.

Systems Thinking books for a deeper dive:

Orchestrating Experiences by Chris Risdon and Patrick Quattlebaum

Closing the Loop: Systems Thinking for Designers by Sheryl Cababa

Thinking in Systems, a Primer by Donella H. Meadows. Her website is rich with resources.

These books guided me as I learned to apply systems thinking at work.

I wrote this article because these processes fell apart amidst real world constraints, but I’d still encourage reading them so you can expand your toolset, picking, choosing, and adapting as needed.